The UPC have used prosecution history in claim construction – what does this mean and what do other courts do?

Towards the end of last year, the Munich Local Division (MLD) of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) issued its Decision in SES-Imagotag SA v Hanshow Technology Co. Ltd rejecting preliminary measures regarding the alleged infringement of European Patent EP3883277 (EP’277).

This is the first time that the UPC has thoroughly considered claim construction. The outcome of the case was somewhat surprising because the prosecution history was used to interpret the granted claims of the patent.

The Decision and its implications on claim construction at the UPC are summarised below. As are the approaches taken by various national courts, for comparison.

The case

SES requested a preliminary injunction against Hanshow, citing infringement of EP’277. In response, Hanshow denied infringement and challenged validity.

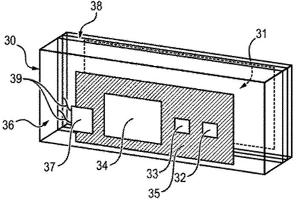

Claim 1 as granted of the patent in question is directed to an electronic label for a sales area. Various features of the electronic label are specified in claim 1, but the critical ones for this case are:

- A display screen;

- A printed circuit board (PCB) housed in a housing on the side of the rear surface of the housing;

- An antenna of a radio frequency peripheral device located on or in a housing on the side of the front surface of the electronic tag.

Figure 3 of the EP’277 patent. Housing (30), display screen (31), PCB (35), radio frequency peripheral device (36) comprising antenna (38).

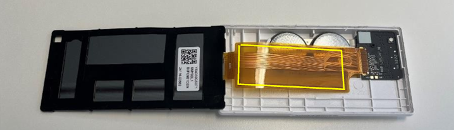

Hanshow’s alleged infringing article comprised a PCB and an antenna, in which a substantial part of the antenna rested on the rear side of a case of the product.

Alleged infringing article comprising an antenna attached to the rear of the foil that is marked in yellow.

At issue was the limitations placed on the spatial arrangement of the PCB and antenna by the claim.

SES argued that the skilled person would understand from the description and figures that the claims did not require the PCB to be in contact with or mounted directly on the housing. Instead, the PCB could be located slightly away from the housing. Similarly, SES argued that other components could be placed in front of the antenna (i.e. between the antenna and the front face). This interpretation would appear to encompass the alleged infringing article.

Hanshow, on the other hand, argued that the PCB must be technically and functionally aligned with the rear side of the housing and assigned to it. Hanshow also argued that it was a core aspect of the invention that additional elements between the front surface and the antenna should be avoided as a matter of principle in order to achieve an optimal wireless connection. As such the antenna of claim 1 had to be positioned in front of the display screen. This interpretation would appear to not encompass the alleged infringing article.

Turning to the prosecution history

To aid their construction of claim 1, the MLD turned to the prosecution history of the EP’277 patent – i.e. the proceedings between the patent applicant and the patent office from filing the application to patent grant. In particular, the MLD looked at the wording of the claims as filed.

The originally filed wording of claim 1 included a statement that an electronic chip on the printed circuit board is arranged at a distance from the antenna. The MLD said that the technical purpose of the spacing was to limit interference and so the wording of the granted claim should be interpreted as requiring the antenna and PCB to be arranged to a certain extent diametrically from each other.

The court found no infringement because the antenna of the allegedly infringing product was at least in part resting on the rear side of the case and so could not also be on the front side of the electronic label.

A surprising approach?

It is significant, and somewhat surprising, that the MLD chose to look at the prosecution history of the EP’277 patent when considering claim construction.

It might have been expected that the UPC would follow the EPO’s well-established practice in claim interpretation in which the file wrapper and original claim wording is not relevant when interpreting the granted claims. However, the MLD chose to diverge from EPO practice.

The legally qualified judge in this case is also a patent judge at the District Court of The Hague, a court which has previously used prosecution history in claim construction. It seems this is the reason such an approach was taken. However, the decision does not provide justification for the Dutch approach to be followed by the MLD. This is particularly perplexing given that the MLD is based in Germany and the German approach currently is generally to not consider prosecution history in claim construction.

Implications

It remains to be seen whether the UPC will settle on an approach in which prosecution history is used in claim construction. The patentee has appealed the decision and it will be interesting to see whether the approach taken at first instance will be followed. It may still be that subsequent UPC case law leans towards a more EPO-like approach of interpreting the claims without regard to the prosecution history. However, it will likely be some time until a harmonized approach emerges.

The Decision and its aftermath highlight the possible unpredictability of a new court system like the UPC. The potential for unpredictability has meant many patent practitioners and patent proprietors have so far been cautious of the new system. There are many positives of the Unitary Patent and UPC, not least a relatively low cost for wide territorial protection across much of the EU. However, for now, many would prefer the increased certainty afforded by more established courts for critical cases.

Approaches followed in other jurisdictions

Onsagers has a team of patent attorneys with experience in a wide range of jurisdictions. This therefore seems a good opportunity to outline the approaches followed by different national court systems with regard to prosecution history and claim construction.

Norway

Summary – prosecution history can sometimes be used in claim construction.

It is clear that patent claims shall not be read in isolation, but that that they must be interpreted in line with their context. This is in accordance with § 39 of the Norwegian Patents Act, stating that the scope of protection of a patent is determined by the claims, and that for understanding the claims, guidance can be found in the specification. Also, the preparatory work indicates that the file history may have impact on the interpretation of the claims. For example, in the case that the applicant has defined a word in a specific way in the specification, or they have before the Patent Office argued in line with a certain understanding, they may have difficulties in being heard with another and more comprehensive interpretation in a later infringement or invalidity case (cf. Are Stenvik, Patentrett, 2020, 4. Editions, Cappelen Damm AS (ISBN978-82-60826-3)).

Documents from file history, both from prosecution of Norwegian patent applications as well as prosecution of corresponding patent applications elsewhere are commonly seen in infringement and invalidity cases in Norway. However, it is to the best of our knowledge not many decisions where file history of the patent in suit have had decisive importance for the outcome of the case. It is first of all where a statement from the patent applicant or the Examiner have been made that resulted in limitation of the scope of the claims in order for the patent to be granted in light of prior art, that file history may have impact on the outcome of the case.

(Kari Simonsen – EP Patent Attorney)

Sweden

Summary – prosecution history can sometimes be used in claim construction.

According to Section 39 of the Swedish Patents Act (1967:837), the scope of patent protection is determined by the patent claims. For understanding the patent claims, guidance may be obtained from the description. This provision corresponds to Article 69 (1) EPC and the Protocol on the Interpretation of Art. 69 EPC is also applied. In practise, however, what occurred during the administrative procedure that preceded the grant of the patent can sometimes also be used when interpreting the patent claims. This particularly applies when the patent holder, during the administrative procedure, has expressly advocated a certain interpretation of a patent claim in order to meet a novelty barrier or lack of inventive step. In such a case, as a rule, a different and more favourable interpretation of the patent claim should normally not be allowed.

(Per Reiner – Swedish and EP Patent Attorney)

Germany

Summary – prosecution history generally not used in claim construction.

The file of the application proceedings of the patent are in principle not permissible as a basis for the claim construction because they are not mentioned in § 14 German Patent Act (extent of protection of a claim) and Art. 69 EPC. However, circumstances during application proceedings may be treated as a piece of circumstantial evidence in view of the skilled persons understanding of the patented teachings (Decision “Weichvorrichtung II” X ZR 73/95). According to a recent decision (2022), a broad interpretation resulting from the permissible material for constructing claims cannot be revised simply by referring to a statement made by the patent applicant during the grant procedure (District Court Duesseldorf 4b O 13/17).”

(Rainer Sterthaus – German and EP Patent Attorney)

US

Summary – prosecution history generally is used in claim construction.

In patent litigation in the US, the prosecution history of a patent, along with the specification and the claims, is considered part of the intrinsic evidence upon which interpretation of the claims is primarily based. The prosecution history is also relevant for determining the scope and applicability of non-literal infringement under the so-called “ Doctrine of Equivalents”, as admissions made during the prosecution may create an estoppel effect that limits the patentee’s ability to assert infringement on those grounds.

(Christian Abel – US and EP Patent Attorney)

UK

Summary – prosecution history generally not used in claim construction.

Generally, the UK courts do not to assess the prosecution history of a patent when carrying out claim construction, with Lord Hoffman stating that “life was too short” for this approach in Kirin v Amgen (2005). Actavis v Eli Lilly (2017) opened the possibility of considering prosecution history if an otherwise unclear point can be unambiguously resolved by the prosecution history or if ignoring the contents of the file would be contrary to public interest. However, this rarely happens in practice. Reference to the prosecution history is the exception, and not the rule.

(Joe Henderson – UK and EP Patent Attorney)

Forum shopping

If a patentee has a corresponding patent in multiple jurisdictions, and the infringing act is also taking place in those jurisdictions, then they might want to choose to bring an infringement action in the jurisdiction that is most likely to be favourable to the patentee. For example, the patentee may think a particular court’s approach to claim construction is likely to benefit their case.

Contributors

Kari Simonsen is a European Patent Attorney with more than 20 years’ Life Sciences/Pharmaceutical sector IPR experience.

Per Reiner is, jointly, an Authorised Swedish Patent Attorney, European Patent Attorney and former corporate patent counsel with over 20 years’ IP experience.

Christian specializes in patent drafting and prosecution in the Chemicals, Oil and Gas and Marine Biology/Fisheries sectors.